The Zeigarnik Effect

How just a few open loops overwhelm us and cause us to lose track of the essential.

“I have found that once I have jotted something down I tend to relax and forget it. If I toss the bits into my mind, on the other hand, what needs to be remembered stays while the rest fades into oblivion.”1

–Haruki Murakami

While the core idea of the well-known psychological phenomenon called The Zeigarnik Effect, pronounced zī-ˈgär-Nik-, is relatively easy to grasp, the story behind its “aha” moment resembles folk tales transmitted verbally by the medium of epic songs in times when the written language wasn’t yet invented. Much like fables that get altered with every subsequent conveyance, so was the story of how it all began.

Despite the events taking place as recently as pre-WWII, unravelling the yarn ball of free-form narratives requires a severe archaeological prowess, and even then, the traces become cold discouragingly quickly. Today, we can only portray an approximation of the stage that became the cradle of this seminal finding about the inner cogs of human memory. The details, I’m afraid, will have to be taken with a grain of salt.

For example, it’s unclear whether the incident occurred in a restaurant or a university canteen, who forgot what, who was the first to observe the critical memory-related oddity, and whether these were individuals other than the “gestalt psychology gang”. These gaps had to be filled with the deductions that made guesses, while ignoring some sources that provided incorrect facts. Luckily, they’re only relevant to those considering chronological exactitude a matter of pride. I hope others won’t mind settling for the “meat and potatoes” of this legend. I tried to dig as deep as I could. Here comes my version of the tale.

Rumour Has It

The early 1920s.

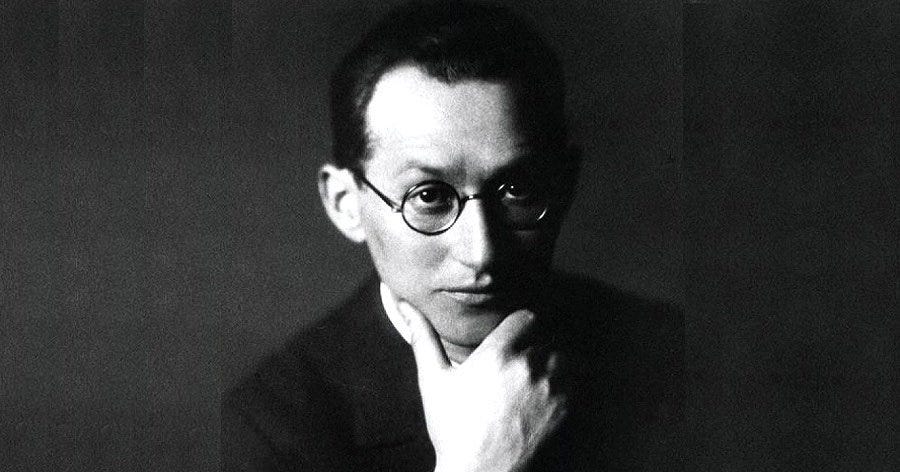

Canteen of the University of Berlin (or any other eatery). Lunchtime (it’s unlikely to have been breakfast or dinner). German-American psychologist Kurt Lewin and his students, Maria Ovsiankina and Bluma Zeigarnik, casually ordered their meals (was this the same group of people?).

The waiter is friendly and efficient. Without writing anything down, he remembers who ordered what and what was or wasn’t paid for. His seemingly impeccable memory impresses Professor Lewin (or Bluma Zeigarnik?).

Once done with the food, they leave the canteen only to realise that one of them (God knows who) forgot a jacket (a bag, or a wallet) and had to return to pick it up. At this historical moment, Mr Lewin (or Ms Zeigarnik) notices a strange phenomenon: the waiter, who appeared to have an almost photographic memory, couldn’t remember who they were!

This was puzzling, to say the least, and couldn’t go unnoticed by hardcore psychologists. A quick questioning of the waiter revealed that they kept information about orders and meal-to-seat mappings in their short-term memories. Once the customers were out, these mental data structures were immediately pruned to “make space” for the new clients.

Kurt Lewin’s (or Zeigarnik’s) observations inspired the Lithuanian-Soviet psychologist Bluma Zeigarnik to conduct a series of experiments that led to what is now known as The Zeigarnik Effect: people tend to remember unfinished or interrupted tasks more effectively than completed ones.

The timing of the theory's establishment was crucial. Bluma was born into a Jewish family and had to be evacuated to Moscow during the Second World War. Access to food was a bit of an issue, let alone hanging out in restaurants. If it weren’t for luck, the phenomenon would have been coined much later by someone else (if at all), and there might not have been any need to provide a phonetic spelling of the effect.

Research

Subjects within a wide age range were asked to perform 15 to 22 tasks of a mechanical or cognitive nature, such as stringing beads or solving puzzles. The total amount of activities for each subject was split into two portions. For the first one, the researcher would allow the task to be completed without interruptions. She’d force an interruption and context switch for the second half. By the end of the session, all props would be removed from the subjects’ view, and they’d be asked to jot down as much information as they could remember about the tasks they’d just worked on. Bluma Zeigarnik’s thesis was confirmed through statistical significance: recalling unfinished or interrupted tasks was about twice as high as remembering the finished ones.2

Arguably inspired by the Field Theory established by her professor Kurt Lewin, whose work she greatly admired, she hypothesised that addressing a task creates a “psychic tension” that keeps it in our memories.

Interestingly, Zeigarnik’s experiments have shown that interruptions occurring closer to the middle or end of the solution process had a more significant impact on task recall than those occurring towards the beginning of the exercise. As we progress through the task and the mental pleasure of getting something done becomes progressively more potent, we become more involved, thereby strengthening our commitment to the memory.

Another notable byproduct of Bluma’s series of experiments was the realisation that this phenomenon could be tamed down or amplified depending on the subject’s psychological profile. Participants who could be easily classified as ambitious and high-achievers forgot about tasks they’ve just completed much more quickly. The subjects interpreted task interruption as a sign of failure and “suffered” from an “ego hit, “ making them more likely to remember unfinished tasks.

In 1927, under the supervision of Professor Lewin, Zeigarnik published a paper in the German scientific journal Psychologische Forschung3 explaining her findings. Zeigarnik’s work is another example of the right people being in the right place at the right time4. Kurt Lewin developed his field theory, a foundation for Bluma’s work.

According to this, a task that has already been started establishes a task-specific tension, which improves the cognitive accessibility of the relevant content.

Some consider the results of Zeigarnik’s experiments to be biased. As is often the case in the scientific realm, the experimenter tends to find what he’s looking for. Nobody’s immune to their cognitive biases, and future reproductions of Bluma Zeigarnik’s experiments were not as conclusive as hers.

Such misalignments could stem from certain shortcomings Bluma Zeigarnik noticed throughout her research. She knew the outcome of any given experiment could be warped by the subjects’ ego involved in a task, by the fact that it was difficult to disguise the interruption as not being part of the experiment, and by the subject’s genuine level of aspiration in a given type of task, such as for puzzle-solving amateurs.

Mental disorders were also potential culprits, which made her conduct more inclusive experiments.

Applications

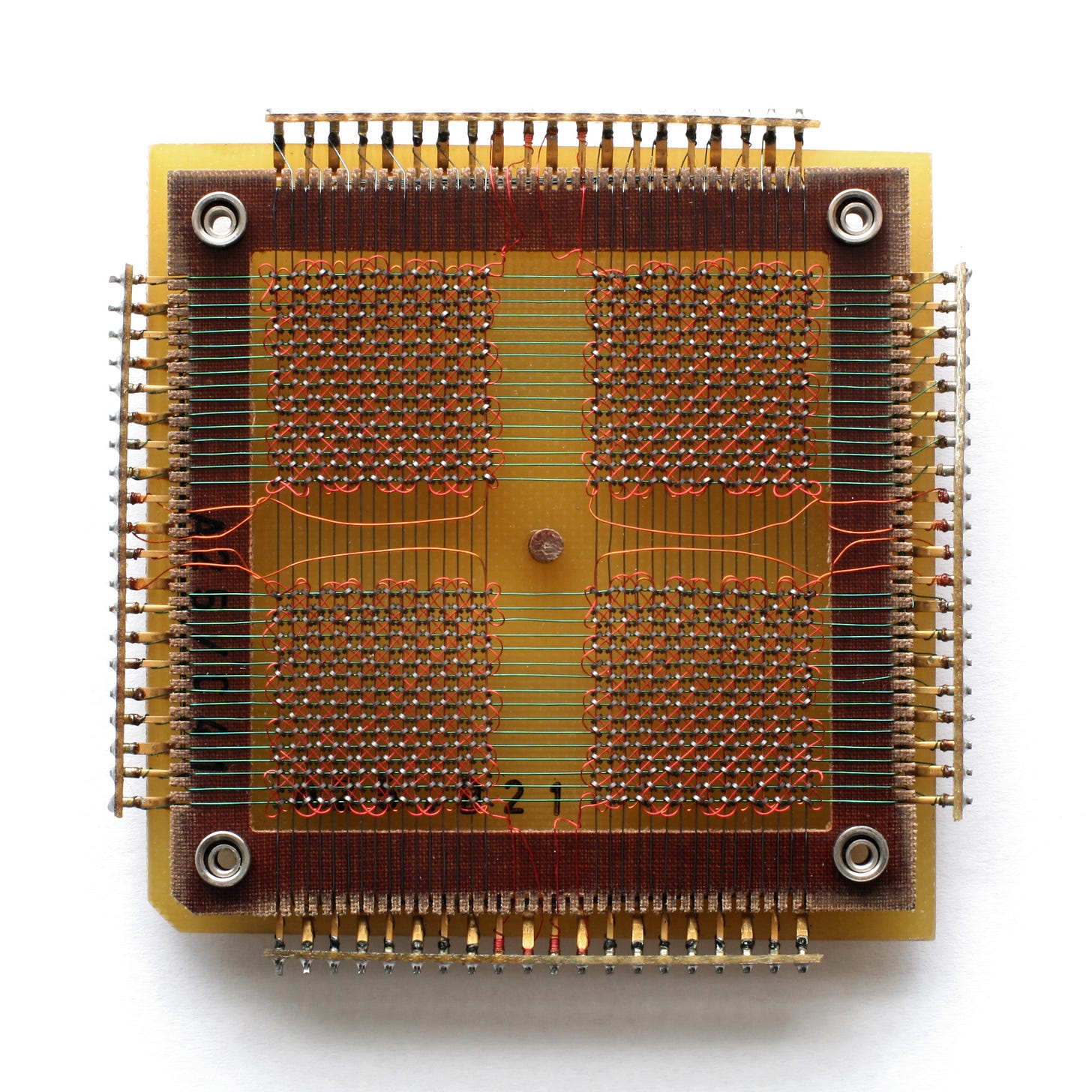

Although comparing people’s brains to the most advanced technology currently available is a very human but flawed approach, I can’t help but notice a lot of resemblance with the way Random Access Memory (RAM), the short-term computer memory, works.

The very first such device was a magnetic-core grid. As long as electric tension is applied to the memory cell, the bit is set to 1. When the transistor is no longer under tension, it returns to its original state of 0.

This is why abruptly switching off your computer can have a profoundly negative and unpredictable impact on the system’s state during its subsequent restoration attempt.

The core idea of applying electrical tension to a mesh of cells has remained almost unchanged since the first RAM, a massive grid of interwoven electrical wires, and today’s minuscule transistor-based microchips.

Mental tension is why keeping secrets, for example, can be challenging and why catharsis or confession can lead to mental relief and even improved health.

“Keeping secrets is physical work. When we try to keep a secret, we must actively hold back or inhibit our thoughts, feelings, or behaviors. Keeping secrets from others means that we must consciously restrain, hold back, or in some way exert effort to not think, feel, or behave.”5

“Disclosure reduces the effects of secrets. The act of disclosing a trauma reduces the physiological work of secrets. During disclosure, the biological stress of holding back is immediately reduced. Over time, if we continue to confront and thereby resolve our emotional upheavals, there will be a lowering of our overall stress level.”6

Other examples of the tension and release’s yin-yang synergy can be spotted in storytelling, TV, advertising, software user interfaces and music. We hold our breaths until the book’s crucible has been resolved. We can’t resist getting to the book’s next chapter if the previous one ends in a so-called “cliffhanger”. We feel as if the song’s missing something. It starts creating tension if it doesn’t return to the fundamental note.

This phenomenon is well understood by those using it.

For example, teachers often ask questions at the end of the lecture to induce a feeling of incompleteness and, hopefully, spark students’ curiosity. They’ll want to be satisfied. Binge-watching or finishing the bag of chips is an urge stemming from psychic tension.

I don’t play video games because an innocent “all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy” quickly turns into a high-priority “finish so-and-so game” to-do item. Today’s games are rarely something you can finish, at least not without spending a chunk of cash on diamonds and virtual swords.

The Zeigarnik Effect is highly monetisable. The fact that our brains feel the tension when unfinished tasks “clutter” our consciousness is a foundation of gamification in software design. For example, the indicator of an incomplete user profile often creates mental tension that prompts you to complete the onboarding process by providing the data the company wants or needs to ensure an ideal user experience.

Try paying attention to this “formula” next time you watch a movie. I bet you’ll start noticing the field theory in every show as if you took the “red pill”. I hope I didn’t make you feel the entire media industry was a big setup. It wasn’t my intention.

It’s not all gloom and doom, though. Lewin and Zeigarnik might have revealed flaws in our memories and unlocked their exploitation potential, but it also allowed us to use them to our advantage.

Forewarned is forearmed. For example, we now know that to get this annoying, continuously looping song from your head, you can listen to it for real once or twice, freeing up some valuable memory space.

We also know that if an unstarted task feels discouraging, you can make a deal with yourself to do it for only a minute or two. If you still want to get out of it by the end of this short timespan, you’re allowed to do so. This reduces the friction between you and what needs to be done. Surprisingly, once you’re two minutes in, you’re much more likely to get it to the finishing line. This is why some writers begin by noodling anything before they get into the zone of writing what has to be written. This is why settling for “just putting the running shoes on” or “only preparing the gym bag” often results in great workouts that would have otherwise been slacked on.

David Allen’s famous book and productivity system, “Getting Things Done”, commonly called GTD, is based almost entirely on embracing the Zeigarnik Effect and hacking it to increase productivity dramatically. In a busy world where professional duties, familial obligations, and other unfinished tasks constantly nag at our minds, fatigue, anxiety, and stress have become almost inextricably linked to the foundations of our daily lives. The author of the system calls such “hanging in the air” tasks “open loops”. Regardless of their criticality, the more open loops you have, the more oppressed you feel, the more you procrastinate, and the more oppressed you feel. This is a vicious cycle most people struggle to escape from. They don’t get enough stimulation from finishing a task, and the overloaded short-term memory grinds their entire life to a halt. Members of the GTD cult who took the time to familiarise themselves with the cognitive impediment studied by Bluma Zeigarnik and implemented science-backed circumvention strategies can certify that this system works.

Hack Your Brain With Notes

I notice this effect in my everyday life, where specific short-term assignments are better off being kept in my working memory to be “flushed” once done. Suppose you’re a student as you’re reading this. In that case, chances are you’re guilty of exhibiting the Zeigarnik Effect in preparing for your examinations and the amount of information that “sticks” once the exam is over.

As it turns out, note-taking is one of the most potent weapons in combating open loops. Our brains don’t differentiate between finishing a task and “parking” it in a location other than its short-term storage. The goal is to release the tension and free up some room in the memory. Fleeting Notes are the solution for one’s randomly emerging thoughts, tasks or anything that must be kept in memory. Literature Notes are the solution for not having to hold the gist of every book you’ve read. Except for individuals capable of remembering up to 300 homogenous facts, most people can only carry about seven thoughts at any time. There’s simply not enough room and willpower to continuously provide the necessary psychic tension to keep their thoughts around indefinitely. The best-selling author

describes the importance of capturing hunches in his book “Where Good Ideas Come From”:“Keeping a slow hunch alive poses challenges on multiple scales. For starters, you have to preserve the hunch in your memory in the dense network of your neurons. Most slow hunches never last long enough to turn into something useful because they pass in and out of our memory too quickly, precisely because they possess a certain murkiness. You get a feeling that there’s an interesting avenue to explore, a problem that might someday lead you to a solution, but then you get distracted by more pressing matters, and the hunch disappears. So part of the secret of hunch cultivation is simple: write everything down.”7

My biggest hope is that you won't forget what you just read once you navigate away…

1 Haruki Murakami, Novelist as a Vocation (National Geographic Books, 2022).

2 Irving B Weiner, and W Edward Craighead, The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology, Volume 4 (John Wiley & Sons, 2010).

3 Kurt Lewin, “Untersuchungen Zur Handlungs-Und Affektpsychologie,” Psychologische Forschung 9, no. 1 (1927).

4 Jim Collins, Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap and Others Don’t (Harper Collins, 2011).

5 James W. Pennebaker, and Joshua M. Smyth, Opening Up By Writing it Down, Third Edition: How Expressive Writing Improves Health and Eases Emotional Pain (Guilford Publications, 2016).

6 James W. Pennebaker, and Joshua M. Smyth, Opening Up By Writing it Down, Third Edition: How Expressive Writing Improves Health and Eases Emotional Pain (Guilford Publications, 2016).

7

, Where Good Ideas Come From (Penguin, 2010).