[Book Review] The Filing Cabinet: A Vertical History of Information

How seemingly insignificant acts of unbinding books, flipping documents on their side and stacking them vertically had transformational effects on knowledge management

Unlike most other countries, the Philippines, where this newsletter issue was written, doesn’t celebrate International Women’s Day on March 8. Instead, the entirety of March is celebrated as Women’s Month. This is a good enough excuse for me to squeeze in a review of Craig Robertson’s fantastic “The Filing Cabinet: A Vertical History of Information1”.

What’s the relationship, you ask? Read on to find out.

Having spent a large portion of my career dealing with data and managing a paperless office that once was paper-full, one thing becomes obvious almost from day one: organisation is key. It’s all about inputs and outputs. You must be able to swiftly file something in its proper place and retrieve it on command just as efficiently. In his bestseller “Getting Things Done”, David Allen said that being organised meant finding things where you expected them to be.

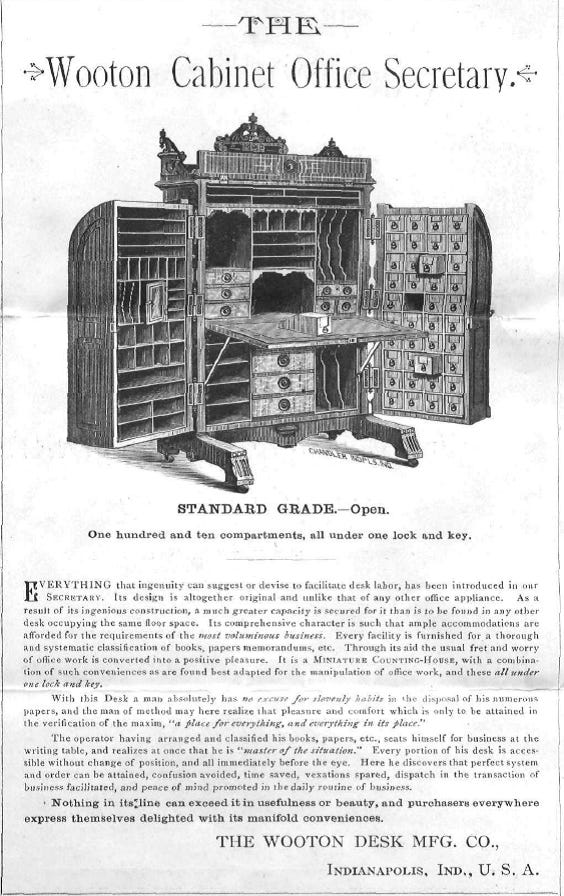

Storage is the enabler of such an organisation, and Craig Robertson’s book is dedicated to its cornerstone: the filing cabinet.

Like many great books, it can be read on different levels of abstraction. You might or might not be interested in the types of metal coating or bearings, for example. Modulate your reading speed until the trail brings you back to the level of detail you’re comfortable with.

On Splitting Books

Although the lion’s share of the writing revolves around filing cabinets, it’s not the only aspect of classification forms you’ll read about. This emanates from the fact that binding related items in books has been a de facto standard for a long time, and unbinding them to transition to a more atomic, granular way of accessing paper has to be understood by the reader first.

The act of bundling or unbundling might sound like not a big deal, but this is what made things like personal computers (instead of mainframes), iTunes (instead of CDs), or TikTok (instead of a full-length movie) possible. Humanity tends to oscillate between two extremities of a spectrum: lumping and splitting. Though both have as many advantages as downsides, each pendulum swing is generally presented as a breakthrough, which often sounds plausible to those who haven’t experienced a few such natural cycles before.

Perhaps the most dramatic example is a friend’s story about his grandfather, who used to be a Russian accountant. Instead of using a regular ledger, he praised the efficiency of working with unbound documents. He promptly changed his mind when it almost got him to jail. This stuff was that important.

A Quick Preview

You can find all of my highlights on the dedicated page of my digital garden, and

’s 205 highlights on GoodReads.However, here are a few noteworthy ones to give you a taste of what’s to come.

No one in the first half of the twentieth century claimed to be living in an “information age”; however, some people increasingly recognized the need to name something different and distinct from knowledge. Sometimes writers identified it by appending a clarifying adjective, using terms such as classified knowledge; others named it data or simply information. The interchangeability of these labels signaled the novelty of this conception of knowledge.

A book, through the permanent binding of pages, was understood to provide integrity in the sense of an undivided or unbroken state.

In one of the earlier issues, we discussed bound vs unbound.

John Durham Peters notes, “No container works best when completely full.

Scholfield called vertical files an “automatic memory”.

Ben Kafka argues, bureaucracy performs an important role in the modern world as an explanation for why people cannot always get what they want.

You can read more about this phenomenon, often called “The Shirky Principle”, on this page of my digital garden.

Women in Knowledge Management

As mentioned at the beginning of the review, women are given extra attention in this book. Indeed, a lot of ink was dedicated to the office romance between female workers and the filing cabinets they had to manipulate daily.

As I was reading the book, my brain replayed scenes from the “Mad Men” TV show, which accurately depicts the office dynamics of that era. It coincides with typewriters, Rolodexes, and filing cabinets in high-rise buildings similar to those vertically stacked cabinets, the analogy Mr Robertson draws throughout the book.

I loved the book, but if I had to point my finger at one annoying thing, it would be the constant hiss of gender inequality that crescendos towards the end. As a classic “Mr Nice Guy2”, Craig seems to be looking at the abovementioned office dynamics through the lens of more modern conventions. Fair enough.

I was raised believing that wishing a “Happy International Women’s Day” was a gentlemanly trait. These days, however, rectifications I receive back, such as “International Women’s RIGHTS Day”, make me take a deep breath before hitting the send button.

I encourage you to read beyond the apparent misogyny of the past and remember that we are where we are today thanks to the monumental heavy lifting of knowledge management that fell upon women’s elegant shoulders.

It’s an excellent read for any knowledge manager, and I hope you’ll enjoy it as much as I did.

Happy Philippines Women’s Month.

Robertson, C. (2021). The Filing Cabinet: A Vertical History of Information.

Glover, R. A. (2022). No More Mr Nice Guy: A Proven Plan for Getting What You Want in Love, Sex, and Life. Sanage Publishing House Llp.