Cameras as Notepads

On taking pictures of parking lot numbers, license plates and post-brainstorming whiteboards.

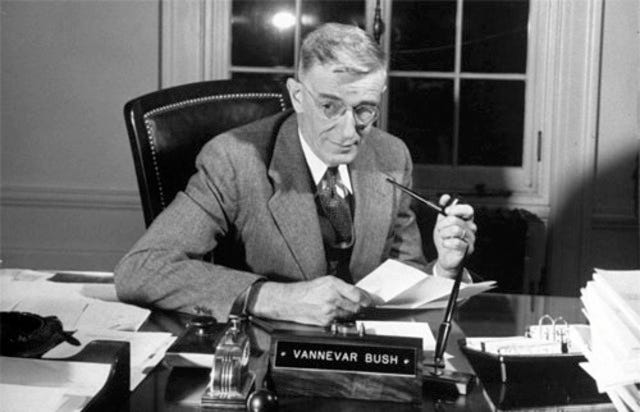

Like his fellow dreamers, Jules Verne and Herbert George Wells, the American engineer, inventor and science administrator, Vannevar Bush predicted a solid chunk of future technology.

Using cameras for information capture rather than artistry was always plausible, but Bush knew they had to become affordable, ubiquitous and portable for this to materialise. In other words, the friction had to be below a certain threshold for photographs to be used as memos. His active participation in the advancement of chemical photography raised a portion of the curtain, hiding the future Adjacent Possible. In the meantime, he fantasized about dramatic future reductions in size, complexity and cost. And he was, sort of, spot on.

A Broadcast from the Past

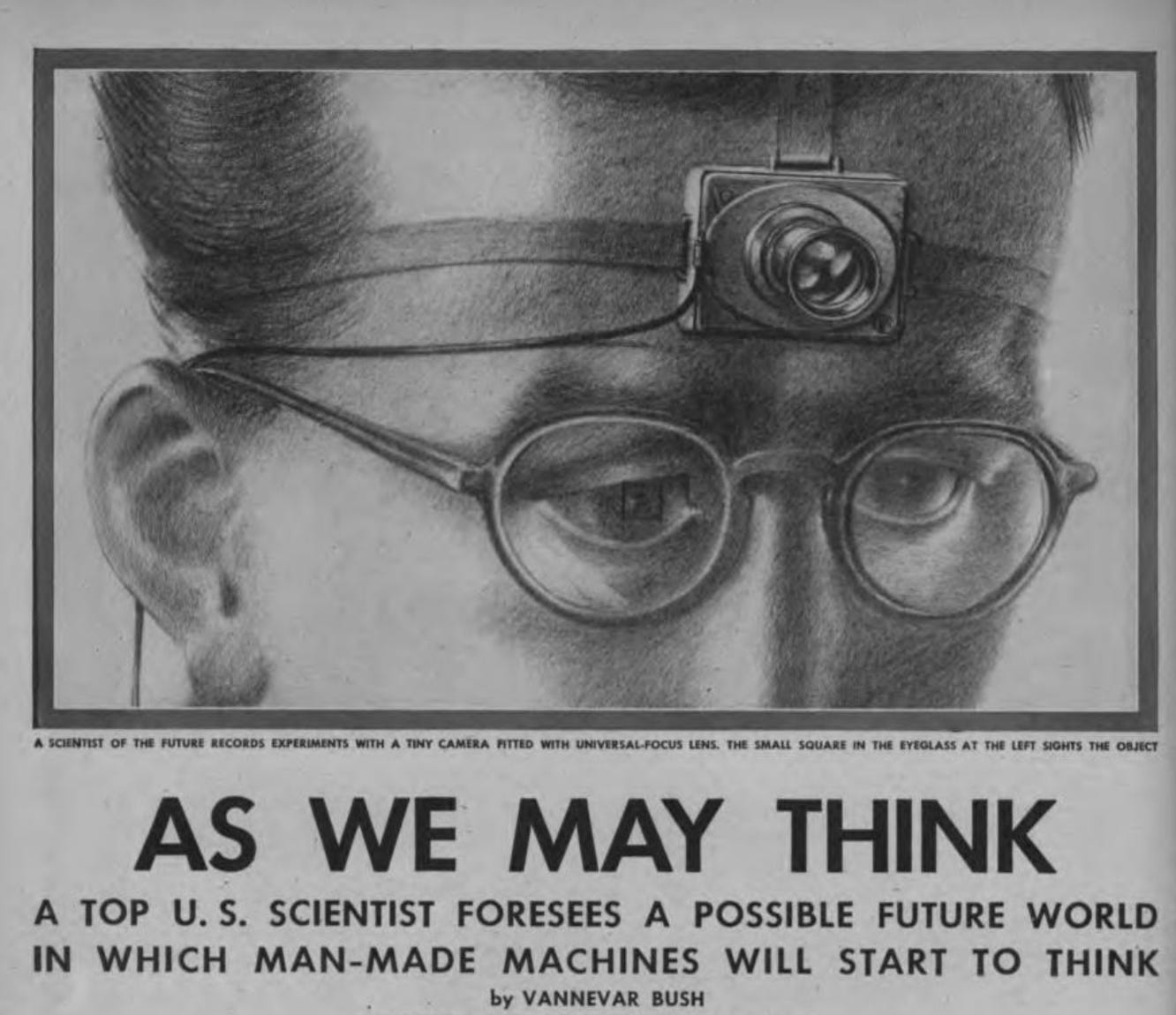

Imagine listening to a crackly monophonic wax cylinder playback as you read the following excerpt from “As We May Think”1, an article he wrote for The Atlantic Monthly in 1945. Hear the enthusiastic narration of Vannevar’s vision of what capturing visual information may look like:

[…] The camera hound of the future wears on his forehead a lump a little larger than a walnut. It takes pictures 3 millimeters square, later to be projected or enlarged, which after all involves only a factor of 10 beyond present practice. The lens is of universal focus, down to any distance accommodated by the unaided eye, simply because it is of short focal length. There is a built-in photocell on the walnut such as we now have on at least one camera, which automatically adjusts exposure for a wide range of illumination. There is film in the walnut for a hundred exposures, and the spring for operating its shutter and shifting its film is wound once for all when the film clip is inserted. It produces its result in full color. It may well be stereoscopic, and record with two spaced glass eyes, for striking improvements in stereoscopic technique are just around the corner.

The cord which trips its shutter may reach down a man's sleeve within easy reach of his fingers. A quick squeeze, and the picture is taken. On a pair of ordinary glasses is a square of fine lines near the top of one lens, where it is out of the way of ordinary vision. When an object appears in that square, it is lined up for its picture. As the scientist of the future moves about the laboratory or the field, every time he looks at something worthy of the record, he trips the shutter and in it goes, without even an audible click. […]

—“As We Might Think”, 1945, The Atlantic Monthly by Vannevar Bush

Did We Get There?

Modern readers, who experienced multiple iterations of mobile devices, camera lenses, and wearables brought to the market by respectable companies, couldn’t help but notice a striking parallel with what Dr. Bush conceptualised in his essay. That point-and-click motion with commoditised instant gratification is far past the “pie in the sky” phase, blowing Vannevar Bush’s predictions out of the water.

Typically, science fiction writers’ and dreamers’ musings are limited by technological advancements of their time. This could be why Bush grossly underestimated the degree of miniaturisation, the number of high-resolution pictures we could store in memory, the wireless camera controls, automatic focus and exposure, and the entire planet's subsequent instant access to the results. Although adjusted for techno-inflation, the above predictions are pretty accurate.

In chapter 9, “Images, Personal Knowledge and Multi-Modal Graphs”, of the book “Personal Knowledge Graphs: Connected thinking to boost productivity, creativity and discovery”,

, the mastermind behind ImageSnippets, describes now-common camera use cases for everyday knowledge management.Our smartphone images are now continuously available as mnemonic aids – magical rewind features for many moments, big and small. It’s also clear that we now use our digital images in increasingly sophisticated ways to augment our cognitive processes.

We grab shots of receipts, recipes, and documents. We take photos of products or parts we want to buy or sell. We take photos of our collectibles and the serial numbers of assets we own. We can even scan photos of our bookshelves and find our books using a typed title.”

Here is the review of this excellent book, previously reviewed in this publication, if you missed it.

We’ve also discussed image capture as a flavour of taking Fleeting Notes.

Be Careful of What You Wish For

Perhaps Vannevar Bush’s most glaring misprediction was that the entire “As We May Think”, in general, and the above excerpt in particular, were utterings of a brilliant engineer trying to portray the post-war world as a place where countries would unite forces in service of scientific breakthroughs, capturing Petri dishes, stalagmites, and important book pages. Instead, devices that outperformed Vannevar’s wildest dreams would mass-produce ultra-sharp cat videos and HD soft porn. As Peter Thiel famously joked during his speech at Yale, “We wanted flying cars. Instead, we got 140 characters”2. It’s difficult to make predictions, especially about the future. You’re almost guaranteed to be wrong, but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try.

I highly recommend you spend fifteen minutes reading the full text of Vannevar Bush’s “As We May Think” because who wouldn’t want to know what was in the post-WWII head of one of the most brilliant engineers who contributed to a massive amount of technology we take for granted today? How many of those prophecies are yet to become a reality?

Bush, V. (1979). As we may think. ACM Sigpc Notes.

https://som.yale.edu/blog/peter-thiel-at-yale-we-wanted-flying-cars-instead-we-got-140-characters

![[Book Review] Personal Knowledge Graphs](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc414461b-75af-46f6-a6e6-9e3c36532343_1000x667.jpeg)