The Corner-Marking Method (Part 1)

One of the rawest marginalia conventions by a busy computer scientist.

After discussing signifiers in the Forever ✱ Notes method, it’s only logical to broaden our horizons by looking at other markup approaches that achieve similar goals.

This time, however, we’re breaking out of the digital realm to open a physical book and make it ours through marginalia, presumably one of the best compliments a reader could make to the author, according to many writers: The Corner-Marking Method by an MIT-trained computer science professor at Georgetown University and author, Cal Newport.

"The Corner-Marking Method" is a collection of conventions used by Cal Newport throughout his reading. It's a tool for thought that'll be right up busy readers' alley when they need to skim through many books. He aims to reduce friction, “chew” through the reading material as quickly as possible, and review the already marked book even faster.

In a way, this approach resembles

's “Progressive Summarisation”, which highlights the transition from coarse bookmarking and highlighting to the laconic excerpts and own writing later.Conventions

When Mr. Newport skims through a book, he uses the following conventions to deploy his hooks:

Slashes

A slash in the upper left/right corner indicates the presence of something important on this page.

The position of the slash is strategic. When flipping through the book's pages with a thumb, this mark will be instantly visible, letting you quickly land on the right page to dig deeper.

Note: This mark could have been skipped unless only one or a couple of words were highlighted per page, which can be easily missed during the flipping.

Square Brackets

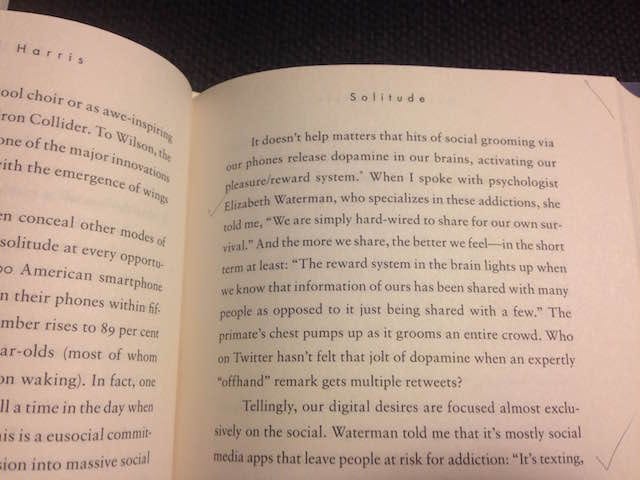

A square bracket on the outside of the paragraph or the lines he thinks are relevant. These lines are why the page gets marked with the slash described before.

Note: as you can see from the image below, sometimes the square bracket turns into a straight vertical line. Perhaps Cal is one of the people who thinks proofreading a manuscript is a suboptimal use of precious time. He pushes the envelope far, saving time by drawing a one-stroke line instead of a three-stroke square bracket. And I’m here writing an entire paragraph on this. I have much to learn from productivity buffs who run a marathon, read one book and write one before their workday begins.

Underlines

Essential names, facts, bits or sentences he particularly likes are being underlined. This convention is used when there's insufficient text to justify using a square bracket mentioned above.

Extras

The following conventions aren't always used but become relevant when Cal Newport writes something and has a thread of ideas in mind.

Stars

A star (or a pentagram, in his case) against the square bracketed or underlined text indicates the "juicy" stuff.

Just like square bracketing and underlining force him to put a slash in the upper right corner, so does the starring of passages. If there's a star against a chunk of text, the entire page gets marked with a star in the upper right corner alongside the slash.

Special Markers

These have no set-in-stone convention and vary depending on their purpose.

For example, imagine him working on a section of a book called “Top Three (fill in the blank)” or whenever his writing includes several arguments defending a specific point. Whenever he comes across something related to number two in his top three rankings, he’ll mark this spot with a circled digit 2.

The Declarative Nature of the Approach

Cal never adds textual annotations or hints as he believes one shouldn't try to help the future self too much. Hopefully, the reader’s brain is not impaired and won’t be later on. It will recall why the passage was highlighted and what to do with it next. It will be able to reconnect the dots upon the following review—no need to spoon-feed it.

This is personality-specific and, therefore, arguable. It always makes me think of the silly example of

and his folder of fleeting notes whose exclamation marks indicate that it was crucial. Still, after a while, Malcolm admits he couldn’t remember the reasons behind the highlight to save his life.Another example is

’s medical condition, which resulted in severe short-term memory loss.Scott Schepper interrupts his reading to create a polished reformulation note of what he found for his analogue slip box ad hoc. You’ll have to decide where to position that slider for yourself.

Other Observations

Convergence Upon Future Re-reading

Cal observed that when working on a new project and returning to the previously annotated book, the same marks would still be relevant to the new work. Since we tend to emphasise things we’re interested in, there’s a high probability of future overlap of highlights. This might result from his Question/Evidence/Conclusion (QEC) trained eye. Sidenote: QEC stands for another one of his frameworks we’ll soon look at. It could also be because people gravitate towards the same things repeatedly. Other readers would have probably highlighted different passages for different reasons, but your highlights generally tend to be similar.

This might be accurate as those familiar with Mr. Newport’s work know that his books are reformulations of the same core idea: reduce distractions to do deep work that moves the needle.

Though it might sound like I’m condemning his publications, this couldn’t be further from the truth. There’s a reason why Ryan Holiday writes only about stoicism, Robert Greene — about power and manipulation, and all of AC/DC’s albums are 12 variations of the same song: it’s comforting, we need this, and we need to hear this from domain experts.

I also consider it a good sign. If you keep gravitating towards the same ideas or are attracted by the same arguments, you’ve probably found your thing, voice, or shtick.

Buying Multiple Copies of the Same Book

Whenever some of the previous annotations aren’t cut for the new book and hinder the reading process, he suggests you simply… buy a new copy. He does that with most of his books. Then again, he's a digital minimalist, not an analogue one. He's also an author who likes the motto "buy more books" for apparent reasons. I know Ryan Holiday "tattoos" his books, too. I've never heard him recommend buying more copies of the same books.

Digital vs Analogue

Cal Newport prefers hardcover books to electronic ones despite the comfort of note extraction and syncing. His dealbreakers are references to electronic locations that are difficult or impossible to use as a bibliography, citations in his writing, and the "cap" on the amount of text you can export for copyright reasons.

Note: Some publishers/editors or journalists, who obviously can't purchase every book every author references, will use Google Books to find the snapshot of the referenced text as part of their due diligence. It's a nice little trade secret.

Using hardcover books reduces the friction of interacting with his information vault. I do resonate with the act of manipulating information kinetically. I'd do the same if I had the same library he does. I think he feels the same way about using the physical artefact as he feels about time-blocking using his analogue time-block planner, which he’s also pedalling.

He does buy ebooks if he doesn't want to wait and needs a book immediately for writing, though. Therefore, it's not uncommon for him to own the ebook and several hardcover copies of the same oeuvre. Sometimes, he buys an electronic version of the hardcover book he already owns. This way, he always has access to it regardless of the circumstances. It goes both ways.

I almost always have an ebook version of the audiobook I appreciate. It rarely goes the other way around, though.

Reading Speed Modulation

He modulates his reading speed depending on whether the material is exciting/relevant or fills up pages. This approach is also advocated in Mortimer Adler's and Charles Van Doren's How to Read a Book1.

I tend to modulate the speed of all information absorption, whether it’s a YouTube video, an audiobook, a podcast, or anything written. Though, once more, our speed modulations may be incomparable in magnitude.

In the meantime, you can learn more about the system through the following first-hand video.

That’s it for this week, knowledge engineers. Next week, we’ll discuss how those who cherish their books and keep them pristine can still annotate them non-destructively.

Adler, M. J., & Doren, C. V. (1972). How to Read a Book. Simon and Schuster.