Learn Chinese Like an Engineer (Part 4)

Plotting a map of your vocabulary by collecting and connecting words and their components. Leveraging the power of knowledge graphs to learn languages.

This is the final part of the series about personal knowledge management engineering techniques applied to learning a language.

Read the introduction, part 1, part 2 and part 3.

This is Mandarin Chinese.

It’s a bold statement, but it’s sort of true. We all carry a knowledge map of word associations in our heads without even realising it. However, whenever someone sees the map above, they immediately resonate with it because this is how our memory works. It’s how we think. Brains are association machines, and, as discussed in the earlier parts of this series, new information (read new dots) is easier to remember if you can connect them to already existing information (read already present dots).

We’ve talked about it previously here.

森林 vs 木 (Forest for the Trees)

The bird’s view in the image above provides the kind of zooming out you need not to lose sight of the forest for the trees. You can’t identify every individual node, but you can immediately notice influential nodes (hubs) that exercise a lot of gravitational pull on other related nodes.

In the last part, we’ve reviewed the Lego-like nature of Chinese, where new words are created by combining other words or their parts, also called components. This would make any engineer immediately recognise the CDD pattern or Component-Driven Development in language learning.

Spend a few seconds looking at both words in the title of this section. Does it make sense even though you’ve never seen them before? Can you spot the component used to create a new word?

It would also reveal yet-to-be-connected words, shown as “orphans” on the knowledge graph. This indicates that the word was encountered but isn’t mastered yet. From the zoomed-out helicopter view, you can drill down into them and actively think about ways to connect them to your current vocabulary. This is how you ensure better memorisation.

To do so, you’ll first identify the components from which this orphan word is built and then attempt to create a vivid mnemonic story to imprint it in your memory forever, as we’ve done in the last post. This process is referred to in linguistics as encoding. A highly connected word in the vocabulary graph is a strong indicator of solid encoding and, as a result, a faster retrieval when you need it.

Let’s zoom into one such influential node: 人.

The word 人 (rén), or person, is an essential component from which many other words are built. Unsurprisingly, it looks like a walking man.

By carefully inspecting the above image, you might not see how 人 (rén) [person] would be connected to, say, 仙 (xiān) [immortal]. That’s because many components have a version that allows them to be “squeezed” into the square shape of a Chinese character. Therefore, 人 often becomes 亻. In the last example, 仙 is 亻+ 山. A person ascends a mountain towards heaven to become immortal. As you can see, both characters were somewhat squashed to become rectangles fitting into the typical Chinese glyph square. Once you know this, the screenshot above should make more sense.

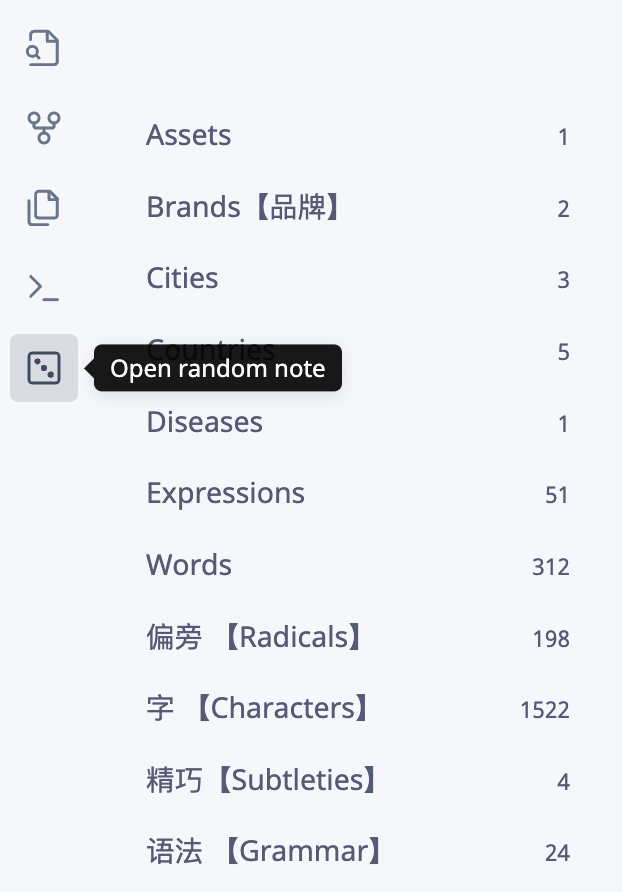

The system you see above is my notebook, personal dictionary, flashcards, and one-stop-shop vocabulary memorisation machine. While working with this application, I can review my notes flashcard style by “rolling the dice”.

We’ve discussed the importance of periodic reviews in one of the earlier issues.

I can add/remove and connect/disconnect my words as my understanding of the language deepens. Most importantly, I can drill down into words and do what’s required to encode them into my memory properly.

The above screenshot of one of the cards gives you an overview of the word 鸡蛋 (jīdàn), or chicken egg. By creating this encoding, I had to actively think about all of its components and construct a mnemonic to remember the word chicken egg and all its components I’m guaranteed to need later.

This is how engineers circumvent the brute-force technique of rote memorisation to increase the speed of foreign vocabulary acquisition dramatically. It’s active, deep learning mixed with periodic revision.

Engage with the information you acquire. Make it part of your personal knowledge graph. See how fast you can retrieve it. Observe how fast you can learn more.

Conclusion

Little did I know that almost six years after I had a friendly chat with my good friend from New York, I’d be seriously implementing an idea she playfully threw in the air that day: connecting Chinese words.

I was too early in my learning journey to appreciate the power of such a simple act at that point. I knew very little about knowledge graphs besides the university algorithmic curriculum and graph databases-related work as a CTO of a podcasting startup. But all pieces of the puzzle fell into place after a while, and after one failed attempt, I decided to try again, and I certainly don’t regret it.

“Learn Chinese Like an Engineer” is this publication's longest-running issue series. But the topic is vast, and I didn’t want it to feel overwhelming. If it did, nonetheless, do let me know in the comments. The Mechanics of Knowledge Management is here to help you in your PKM journey first and foremost, so do chime in to steer it in the right direction.

The system described in this issue is a private tool I’ve been building for a while. Much effort went into it, and if you think you might benefit from it, let me know in the comments, and I’ll consider publishing it for free for all to use.

Thanks for giving this series a chance (even if you’re not studying a foreign language).

Happy knowledge management.