Learn Chinese Like an Engineer (Part 1)

Cracking the toughest ancient linguistic nut with tried-and-true engineering tools.

There’s a reason last week’s issue was dedicated to what I like calling “The Onion Layers of Knowledge”. We needed to discuss the inside-out build-up paradigm of knowledge acquisition because it’ll help us dive into the engineering approach to learning any foreign language.

I started learning Mandarin Chinese a few years ago. As is often the case with projects whose timeline is measured in decades, it was a motivational roller coaster. It still is to a great extent, though, over time, it becomes increasingly easier to add new onion layers on top of others. With that, staying motivated becomes more manageable, too. The more you master something, the more motivated you become.

Like real onions, those knowledge layers also tend to be thicker, more robust, and more significant.

Not All Words Are Equal in a Language

In any language (even a programming one), the importance of words in the total vocabulary is never distributed equally. Instead, a subset of it is indispensable, another superset is sufficient, and subsequent, bigger supersets elevate your command of the language, promoting you to the ranks of elite speakers.

You can picture it as a diagram comprised of concentric circles.

The innermost circle represents that seminal group of words, such as “you”, “and”, “with”, “not”, etc. You can’t reasonably function in any language without core concepts of time, attribution, direction or indication. Without this core inner circle, there can be no subsequent layering of knowledge.

In the middle, you’ll have heavily used words that won’t necessarily be required in almost every sentence. For example, “ship”, “flower”, “earth”, etc. You’ll still be able to express yourself, but until this inner circle is of a reasonable thickness, you’ll sound clunky to native speakers.1

Once you’ve beefed up this slice, you can consider yourself proficient and literate. You can go about your life, have native-speaking friends, read, write and work. This is where many either slow down the learning process or stop it altogether. This is not to be condemned at all. Perhaps this is all you ever needed. People’s ambitions and expectations vary, and rightfully so.

However, this level of proficiency might not be sufficient to access high-quality information, people and jobs. Therefore, you might want to push the envelope further to enrich the vocabulary with words like “nebulous”, “contingent”, or “plagiarised”. This will be the last, ever-expanding concentric circle of the language.

Word Distribution in Mandarin Chinese

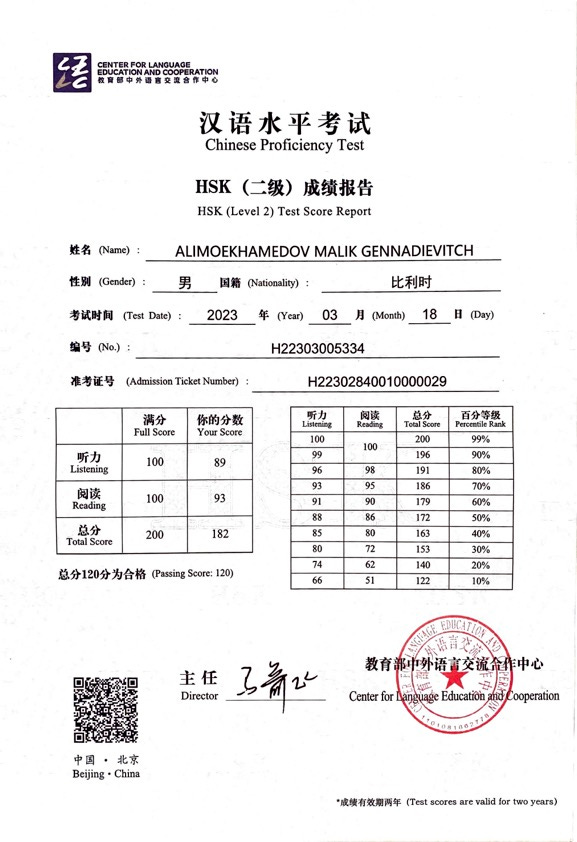

When you become serious about learning Chinese and measure your knowledge with an agreed-upon official yardstick, you’ll quickly discover HSK (Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi) or the Chinese Proficiency Test. This test has six levels, where the first two correspond to that central inner circle, HSK 3 and HSK 4 are the middle superset circle, and HSK 5 and 6 certify your advanced mastery of it.

The very first level requires you to know 150 fundamental characters. The second level adds another 300 to the pile. Those 450 characters are considered crucial, though you might find only later why they are classified as such. For example, staples, such as 的 (de) “of” and 不 (bù) “not”, are part of this must-have kit.

The biggest criterion for labelling a character as fundamental is its usage frequency. By analysing typical conversations and writing, linguists could score Chinese characters by their average frequency of use, making it easy to determine what new learners should learn first.

Not a Leisurely Walk

Mandarin Chinese is ranked in the IV difficulty language group by FSI (The Foreign Service Institute). There are only four groups if you’re wondering. Chinese is, by far, one of the most difficult languages on earth, along with Arabic, Japanese, and Korean.

It’s an ancient, unconventional, context-specific, nuanced, complex tonal language that requires approximately 88 weeks (2200 hours) of practice to reach a decent level of proficiency2, let alone mastery. There’s a reason why Google Translate fails miserably at it. There are many moving parts, and we’re not even talking about its sophisticated writing system.

So, it’s not surprising that Russians use the expression “Chinese grammar” to classify something as insurmountably opaque.

But there is an engineering way to crack this nut much quicker than following a traditional learning path. A way that applies database management paradigms and modular software design approach to language learning. It might not be for everyone, but it certainly will resonate with those whose brains are wired in a certain way.

I’d like to share it with you in the next issue. Stay tuned…

https://chameleonmemes.com/hilarious-examples-of-bad-english-memes/

https://blog.rosettastone.com/the-complete-list-of-language-difficulty-rankings/